Slice is how private investors go early.

The best returns don’t come from writing checks into big names. They come from getting in first.

Slice backs emerging managers before they become headlines.

A curated portfolio of first-check venture funds—shared access, zero compromise.

On data rooms

We focus on managers with fresh operator backgrounds, and see a lot of the same mistakes over and over. Raising a fund is not the same as raising for a startup. This piece is meant to guide you in how to think about your data room, what matters and what doesn't.

Good data rooms show, rather than tell, your ability to track multiple cap tables, maintain founder relationships at scale, and report accurately on the good, the bad and the ugly with candor and precision. Only three documents matter: a deck, a schedule of investments (SOI), and a bunch of LP letters.

Decks are (mostly) marketing fluff

The best decks answer only one question: what's your clear right to win, and how does it translate into access?

Many first-time managers default to autobiographies. It's understandable. Operators spend years building credibility through experience. But the right partner will have done that homework already, the key question that's not obvious from your LinkedIn profile is: how can this person source and win deals ahead of large platforms?

Lead with a clear thesis. Sourcing model, investment criteria, how you add unique value. Your biography matters as proof of thesis, not as the thesis itself.

SOI is the proof your marketing isn't just fluff

Most managers spend more time on the deck than the SOI. Do the opposite. At the end of the day, LPs are buying a basket of assets, and the SOI best represents that basket.

The most common gap we see is dilution tracking. A company's valuation goes up 10x, you report a 10x markup. But the math tells a different story. Your $100K check at a $5M post-money is now at $50M, but you've been diluted from 2% to 1.2%. Your position is worth $600K, not $1M. Actual value is ownership times valuation, not investment times valuation multiple.

You can count on one hand how many managers actually compute dilution from real share counts across rounds. Most report gross markups and move on. When you track it precisely, you're signaling something: you're in the weeds, you have cap table access, you maintain the relationships that give you that level of detail.

Early-stage portfolios are messy. Companies die, rounds get complicated, information becomes stale. The managers who stand out have systems for tracking it anyway. If you can't properly organize your own portfolio data, managing twenty companies becomes overwhelming fast. The SOI shows whether you have control of the information, whether you seek it, track it, and report it accurately.

Don't be shy about including your angel investments either. Everything tells a story. LPs want to see how your thinking has evolved, whether your current investing style matches what you're pitching for the fund. And make sourcing visible. Where did the deal come from? How did you get access? Why did you make the investment? Context is as important as the valuation.

LP Letters show soft power

The LP letter is a relationship proxy. It shows how you stay close to twenty founders simultaneously. The best ones are specific: ownership stakes, competitive dynamics, cap table composition, what's actually happening with the business. They also include a snapshot of the SOI at the top: current ownership, valuations, recent activity. It makes the letter useful as a standalone document.

The weakest read like press releases. Everything is wonderful, everything is great, everything is good. It can't all be good all the time. You can tell when a manager is just copying and pasting from the founder's latest update email. There's no analysis, no context, no point of view on what it all actually means. The letter becomes a forwarding service, that's not what you charge your customers 2/20 for.

There's a tendency to spend LP letters talking about things that don't directly matter: long preambles, general market commentary inspired by the latest twitter feud, personal matters that don't relate to the business or underlying portfolio. Focus on what value are you bringing that makes your founders want to keep you at their table. And stay consistent. Some send ten pages one quarter, two paragraphs the next. There is clear signal in the noise, and it speaks volumes about how you operate.

DO THEIR HOMEWORK

You can learn a lot about a manager before you spend quality time with them, just by how they present their data.

The medium is part of the message. An open link to a raw spreadsheet signals trust. Excel files on DocSend with no look-through formulas or download permissions create unnecessary friction. Don't force your prospect to ask permission for something they already have expressed interest to review in detail. If you're not comfortable sharing your data with a prospect, chances are you're not truly sold on having them as a partner.

Your materials tell a story. Make sure it's the story you want to tell. Most importantly make it easy. Do their homework, no great chef expects their customers to cook their own meal.

In the spirit of this last pearl of wisdom.. we've built a template for the ultimate SOI because it's the document that varies most and matters most. Don't be shy, reach out if you'd like more tips. We are built different at Slice :)

The great bifurcation

Venture capital is unrecognizable from what it was a decade ago. Two seemingly unrelated innovations obliterated the old regime: Y Combinator's SAFE note in 2013 and SoftBank's Vision Fund in 2017. While the SAFE democratized raising venture capital, making it easier for founders to get funding earlier than ever SoftBank made it so costly to compete at scale that only infinite capital could win.

Everyone got squeezed in the middle of these two invisible macro forces with legacy investors pushed to raise bigger vehicles chasing fewer opportunities.. driving prices to insanity, and most importantly creating a vacuum at the earlier stage where a new wave of managers is writing a new chapter in the history of the asset class.

YC claim to fame

Before 2013, raising your first round was prohibitively expensive. Founders would spend upwards of $50k in legal fees driven by lengthy negotiations over liquidation preferences, board seats, veto rights, and all the trimmings that come with proper governance. Months of runway burnt on paperwork for a company that might not even exist in a few weeks.

Convertible notes existed but came with ways for investors to take control when things went sideways. Worse, they were ontologically wrong. Debt instruments in an equity game? As Carolynn Levy, the SAFE's creator, put it: "Do you want to start your relationship off with your investor arguing whether interest should be 3% or 10%? That is just not good for the ecosystem."

Then in the winter of 2013, YC dropped the SAFE. Five pages. No security. No governance rights. No board seats. No interest rates. No maturity dates. Just "give us money now, we'll figure out what it's worth later."

The SAFE went instantly viral. Anyone could download it from YC's website and use it to raise capital at no cost. It became the standard for seed rounds, making early-stage capital an undifferentiated commodity where speed is the only thing that matters.

Masa’s Nuclear Submarine

Four years later, SoftBank launched a $100 billion venture fund. Putting this in perspective: global VC deployment that year was $200 billion. U.S. deployment was $84 billion. Masa rolled up enough capital to match the entire American venture industry and then some.

This wasn't just bigger checks, but an existential threat for storied venture firms such as Kleiner, Sequoia, Benchmark, and the likes. Every multi-stage fund suddenly faced the same faith: scale up or get priced out. When your competitor can write $100 million checks without blinking an eye, your $10 million lead commitment just won’t get attention of the most ambitious founders.

The industry response was swift. Driven in part by the run-up of adoption across SaaS, Fintech and Cloud, fund sizes exploded as everyone raised bigger vehicles to compete for the same later stage deals. Unit economics became optional. Profitability became something you worried about "eventually." The entire startup playbook shifted from "get to liquidity asap" to "as long as you grow fast(est), Masa will fund you."

SoftBank didn't just inflate valuations, they proved private markets could provide infinite capital.

The great bifurcation

These two innovations created the venture landscape we're in today. Investors had to choose a path: go micro (capitalizing on the SAFE note) or go mega (competing at Vision Fund scale).

Multi-billion dollar funds can't return on single-digit billion exits so they stopped showing up early. They wait for breakout signals, write bigger checks into safer bets, and manufacture returns through concentration.

Early stage got commoditized. Every seed fund writes similar checks on the same terms at similar valuations. Differentiation is access, speed, and what happens after the wire. The entire middle collapsed. The old guard can't play small, their economics don't work. Traditional seed funds can't compete with platforms that have infinite capital and zero price sensitivity. What's left is a barbell: mega-funds writing $50M+ checks into growth, and a fragmented network of angels and emerging managers writing true first checks.

That's not a gap. That's the opportunity. The alpha didn't disappear, it migrated. To companies raising $500K on a SAFE before anyone's heard of them. To founders building in stealth for 18 months before they need venture. To managers who move first because they're not dragging a $500M fund behind them. If you're an LP after venture-sized returns, you can't write bigger checks into brand-name funds and hope they time it right. You need to go where platforms can't: emerging managers with sub-$20M funds writing first checks into companies no one else sees yet.

The best stay private forever

IPOs aren’t the goal anymore. For the best founders, they’re a distraction. Something you do when you have no other choice. The headaches are bigger, and the rewards don’t justify the tradeoffs. The truth is, great companies don’t need to go public anymore. So they don’t.

Hit your quarter, stay out of the headlines, keep analysts happy. It’s a system that punishes long-term thinking. Even the best operators—Musk, Bezos, Sundar—are stuck playing defense. Layer on regulatory complexity, ESG reporting, activist investors, and it’s clear: if you don’t have to IPO, you shouldn’t.

Private Capital Has Changed the Game

There was a time when public markets were the only way to raise meaningful growth capital. That era is over. Since the GFC, venture AUM has exploded from $300B to over $3T. What was once boutique is now institutionalized, and for good reasons. Excluding returns from the big tech growth stocks public market returns suck. No surprise that during the same period of time we’ve seen privates assets ballon in size, the number of publicly listed companies shrunk over 10%.

Today, late-stage private rounds routinely hit $500M+. These used to be exclusive domain of public-markets. Now they’re happening behind closed doors, led by crossovers, sovereigns, and pension funds who need exposure to the best growth stories to keep up with their obligations.

Just like growth capital, liquidity for early team and investors used to be a big reason to go public. But neither is true anymore. Secondaries have exploded in popularity to become a real liquidity path for anyone that needs it. SpaceX, Stripe, OpenAI, Databricks proved it many times over: for the companies where demand exceeds primary supply, secondaries clear at or above the last round price.

Permanent Capital Wins

Thrive, Coatue, Sequoia, Tiger—they’re not venture funds in the traditional sense. They’re permanent capital platforms. They don’t need to exit. They’re not playing for DPI. They’re building Blackstone-like positions in the best private companies and holding for as long as they want.

There’s no more room at that table. The franchise window is closed. Just like there won’t be another Vanguard or Fidelity, there won’t be another Sequoia. Competing with these platforms at growth is a losing game. If you’re not already in the round, you’re not getting in.

So What Now?

For retail investors? The door’s mostly shut. The Mag 7 carried the S&P for the last decade. Once that’s done, there’s not another class of mega-cap IPOs waiting in the wings. Most of the upside has already been captured in private.

But for family offices and UHNW investors, the strategy is clear: barbell it. (1) Anchor on late-stage private positions with public-like multiples. (2) Get in early where possible, through networks and operator-led pre-seeds. (3) Use secondaries as a way in, not just a way out.

Liquidity is no longer a finish line—it’s a tool. For early-stage investors, secondaries aren’t an emergency exit. They’re capital recycling. They’re what lets you keep playing, keep backing the next one, and compound winners before the market ever gets a taste.

The Old Playbook Is Over

Venture used to be: fund managers, wait for IPOs, return capital, rinse, repeat. That model doesn’t work anymore. The best companies aren’t exiting, and capital sitting on the sidelines is just getting diluted.

We’re in a new era. The ones who adapt will own it. Everyone else will just keep waiting.

Unbundling the accelerator

Accelerators are no longer relevant. YC, Techstars, 500 Startups, and their copycats feel less like launchpads and more like abandoned malls. The signs are still up but the crowd’s moved on.

What used to be a golden ticket now reads like an equity-taxing detour. YC might be the exception but even that’s debatable. At this point the orange badge, is less about validating ideas and more about pricing them.

The first step? Not anymore.

The best founders don’t care for the vanity, and since they are the best at what they do, the right networks tend to form naturally around them. They raise their first check through a mix of angels and small funds providing highly personalized feedback, intros and hands-on help compared to the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach of most accelerators.

What accelerators offer: early capital, community, mentorship is still very much needed but has now been unbundled and redistributed across networks of operator-led syndicates, rolling funds, and micro-funds.

First Check ≠ First Round

If anything, the most lasting legacy of the accelerator era won’t be the platforms nor the mafias, but rather the popularization of SAFE-like instruments which decoupled the first check from the first priced round. This generational shift opened the door to a new form of first-check investing that’s now widely accepted as the standard, though its implications remain wildly under appreciated and not nearly enough debated by LPs.

Venture capital has long sold the idea that early risk equals outlier return. But as funds succeed, they scale. And as AUM scales, risk appetite shrinks. In the last cycle, early-stage managers had to show up first because there simply there was no infrastructure for anything earlier. Seed was truly the first capital, and valuations reflected that.

Today, thanks to bigger checkbooks, stronger brands, and more layers to the capital stack (to the SAFE point mentioned above), many early stage funds can afford to show up second, or even third. To nobody’s surprise this has translated in seed valuations more than doubling over the last five years, with most rounds now landing between $15–$20M and many pushing past $30M in valuation. But that’s not just inflation, it’s reclassification.

This has led to the in-adverted consequence of pushing early stage funds to compete with multi-stage platforms: chasing breakout signals, showing up late, and deploying larger checks into companies that are mostly de-risked. Meanwhile, the real upside, zero-to-one, is happening elsewhere. Some call it pre-seed. We call it first-check.

This is what disruption looks like.

Great companies don’t start at $30M of valuation. There’s always a round before. Probably two. But those rounds are increasingly impractical for traditional funds, leaving the door wide open instead for networks of angels and ex-founders who have the opposite problem of larger funds, their check sizes are too small to make sense in later rounds.

But decentralization isn’t without tradeoffs. As early-stage capital fragments across hundreds of smaller players, signal becomes harder to read and diligence more subjective. For LPs, this creates real noise and strong managers get overlooked while weak ones easily slip through the filters of the old guard. The opportunity is bigger, but so is the complexity.

If you’re an LP, that means you’re buying in at a premium, eroding the very premise of early risk = outlier return. You’re paying more for the same company your managers should have backed a year ago, if they had a smaller fund.

Those same managers are hoping to compete with multi-stage platforms that bring mature brand equity, meaningful platform value, and near-total price insensitivity. They can’t win that fight by nature of still being new to the market and with unproven platforms of their own. Instead, they end up backing the companies that don’t make the cut. And in a market this small, there’s usually a good reason why. It’s not because they were hiding in plain sight. It’s adverse selection.

The alpha remains early, but early looks different now.

The next wave of early stage venture won’t be won by funds with the big checkbooks trying to outsmart the multi-stage platforms at their own game. It’ll be won by those who move first and back founders before it makes any sense for a big check writer to get involved.

This means smaller funds, and true value add beyond just capital and twitter platitudes. And for LPs who want to capture this slice of early stage, it’s not about writing bigger checks. It’s about expanding the surface area. That’s the real challenge for every private investor trying to deploy into this cycle.

Just like these new breed of managers, LPs need to develop conviction earlier backing small teams with a clear edge before there’s enough data to underwrite any claim of fame. That means building new diligence frameworks, accepting longer hold periods, and being willing to trade the illusion of safety for true venture returns.

Long live the seed round

AI is exerting a deflationary force on the cost of starting and scaling a company. You can now build more, faster, with less. The bottleneck isn’t compute—it’s clarity. Talent remains scarce, but when paired with leverage, the right person is worth a team.

Startups used to raise to buy servers. Then the cloud made that cheap. Suddenly, you could spin up infrastructure with a credit card. The constraint shifted down the stack to people. That drove up salaries, pushed founders to dilute earlier, and led us into the era of $5M seed rounds. Now, AI is starting to do to labor what AWS did to hardware: abstract, accelerate, and commoditize.

What used to burn cash now scales with prompts and APIs.

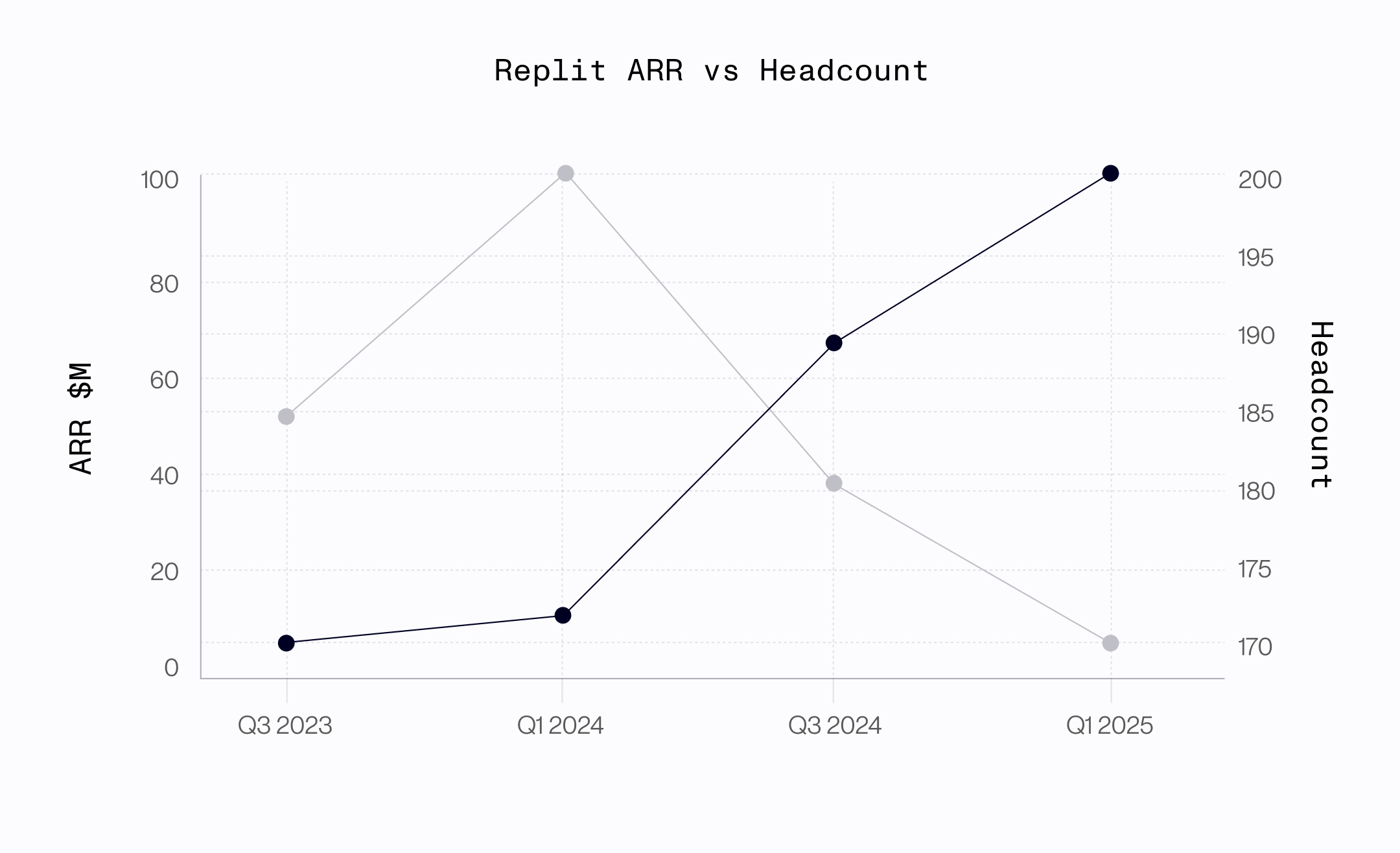

Bolt got to a $700M valuation with 35 people. Replit went from <$10M to $100M+ ARR while shrinking headcount. These are no longer edge cases; they’re what the next wave of founders aspire to. The bar is higher, and the playbook is different.

This new generation is building leaner by default. They’ve internalized what the last cycle taught too late: dilution is expensive and mostly irreversible. If they’re raising, it’s because it’s strategic—not because they need the money.

That’s creating a bifurcation in the market. The best teams are raising less and doing more, which makes early entry more valuable and rarer. Pre-seed checks under $1M are up 17% YoY. In many cases, SAFE rounds under $500K are diluting less than 10%. For most, it’s below 5%.

AI-native teams are expected to hit product-market fit with $500K–$1M. A few are cashflow-positive on day one. These companies don’t need the traditional $2–3M seed round—and increasingly, they’re skipping it altogether. Especially if the capital doesn’t come with real value-add.

Pre-seed is the new seed. Meanwhile, the bloated ZIRP-era seed round is going extinct. That’s bad news for traditional seed funds stuck writing big checks into rounds that don’t want or need them. They’re left fighting multistage platforms for breakout access and losing.

The founders who can run the fastest mile don’t need convincing to raise big. They need a reason. And unless capital can meet them at their velocity and scale, it’ll miss the window completely.

If you’re an investor, this is the game now: write smaller checks earlier, or sit out the next wave of generational companies.